Events

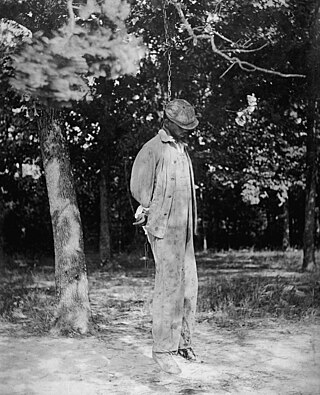

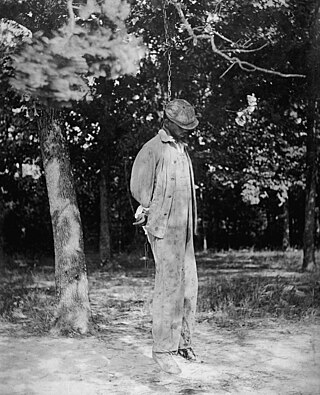

Stacy Pratt McDermott's 1999 article "'An Outrageous Proceeding': A Northern Lynching and the Enforcement of Anti-Lynching Legislation in Illinois, 1905–1910" analyzes the events leading to James's final moments. Pelley's twisted and bruised dead body was found gagged with a cloth in an alley on the morning of November 9. The police chief sent for bloodhounds and used them that day. The dogs led authorities to arrest five people: James, Arthur Alexander, Sam Mosby, Georgia Cooper, and another woman identified only by the surname Green. James and Alexander were the primary suspects. [8]

"James had no alibi for the hour between five and six o'clock on November 8, the time which the coroner's jury thought the murder to have taken place. The flour sack that Green had allegedly been washing upon her arrest matched the gag found in Pelley's mouth. Cooper's alleged statement that she washed James's bloodstained clothes on the night of the murder and James's muscular build added to the limited evidence." [9]

Mobs began to form across the river, and citizens started to "investigate" the crime scene and James's home. The mob began to carry out its own "investigation" of James, since the police force did not align with the mob's desired time frame. [10] Hearing plans of the assembling mobs, the police began to increase security by the jailhouse, and even dismissed several groups of would-be citizen investigators from the crime scene. While the security was effective in keeping the jailhouse secure, the history of social disorder suggested that the mob was only gaining strength and would eventually overpower the guards. Alexander County Sheriff Frank E. Davis and Deputy Thomas Fuller attempted to keep the detainees in the jailhouse safe from the impending invasion. Knowing the mob was targeting James, the two officers took him into the woods on the night of the 9th as the mob began to plan their attack on the town. [5] To avoid the even further inflamed racial tensions in nearby towns, the three stayed in Karnak, Illinois, about 27 miles north of Cairo. Hearing of the officers and James fleeing, 300 men from Cairo boarded a freight train to Karnak. The trio were quickly found and offered little resistance to the mob. The officers were disarmed and the mob kidnapped James. The next day, James, accompanied by the mob, arrived to a waiting crowd of hundreds at the Cairo train depot. McDermott describes his final moments,

The judges, jury, and executioners lifted the rope to avenge the dead woman, but the rope broke and threw James roughly to the ground. As he stood, several people in the crowd riddled his body with approximately five hundred bullets. William James was dead. [...] The mob ran with his bleeding body to the murder scene in the alley. One man chopped off James's head, put it on a pike, and lifted it up for the cheering crowd to see. The mob then set James's body on fire and roasted the remains while men, women, and children shouted and cheered. When the fire died out, the horror continued as people moved in to dismember the body. Some took out their pocketknives and cut off ears and fingers and broke up bones to take as gruesome souvenirs.

—

"An Outrageous Proceeding" [1]

Henry Salzner

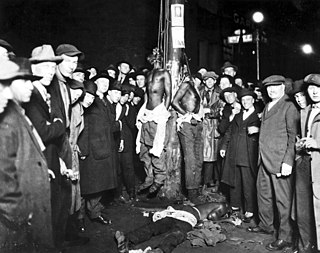

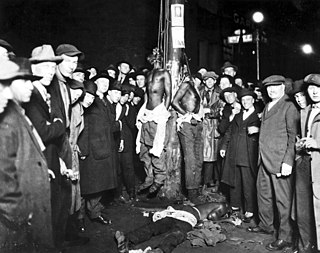

After James was dead, the mob returned to the jail and kidnapped Henry Salzner, a white photographer who was charged with murdering his wife with an axe. Salzner's sentencing was scheduled to be held later that month, but the mob decided to murder him first. Salzner was lynched and shot in the public square. After the second lynching, shouting matches and minor looting gripped Cairo until the next morning when the Illinois National Guard implemented martial law and restored order in the town. [1]

In the broader context of racism in the United States, mass racial violence in the United States consists of ethnic conflicts and race riots, along with such events as:

Alexander County is the southernmost county in the U.S. state of Illinois. As of the 2020 census, the population was 5,240. Its county seat is Cairo and its western boundary is formed by the Mississippi River.

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of informal group social control, and it is often conducted with the display of a public spectacle for maximum intimidation. Instances of lynchings and similar mob violence can be found in all societies.

Cairo is the southernmost city in Illinois and the county seat of Alexander County. A river city, Cairo has the lowest elevation of any location in Illinois and is the only Illinois city to be surrounded by levees. It is in the river-crossed area of Southern Illinois known as "Little Egypt", for which the city is named, after Egypt's capital on the Nile. The city is coterminous with Cairo Precinct.

Charles Samuel Deneen was an American lawyer and Republican politician who served as the 23rd Governor of Illinois, from 1905 to 1913. He was the first Illinois governor to serve two consecutive terms totalling eight years. He was governor during the infamous Springfield race riot of 1908, which he helped put down. He later served as a U.S. Senator from Illinois, from 1925 to 1931. Deneen had previously served as a member of the Illinois House of Representatives from 1892 to 1894. As an attorney, he had been the lead prosecutor in Chicago's infamous Adolph Luetgert murder trial.

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s, slowed during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, and continued until 1981. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimized ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South, as the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states. In 1891, the largest single mass lynching in American history was perpetrated in New Orleans against Italian immigrants.

The Springfield race riot of 1908 consisted of events of mass racial violence committed against African Americans by a mob of about 5,000 white Americans and European immigrants in Springfield, Illinois, between August 14 and 16, 1908. Two black men had been arrested as suspects in a rape, and attempted rape and murder. The alleged victims were two young white women and the father of one of them. When a mob seeking to lynch the men discovered the sheriff had transferred them out of the city, the whites furiously spread out to attack black neighborhoods, murdered black citizens on the streets, and destroyed black businesses and homes. The state militia was called out to quell the rioting.

On June 15, 1920, three African-American circus workers, Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, suspects in an assault case, were taken from the jail and lynched by a White mob of thousands in Duluth, Minnesota. Rumors had circulated that six Black men had raped and robbed a nineteen-year-old White woman. A physician who examined her found no physical evidence of rape.

Crime in Omaha, Nebraska has varied widely, ranging from Omaha's early years as a frontier town with typically widespread gambling and prostitution, to civic expectation of higher standards as the city grew, and contemporary concerns about violent crimes related to gangs and dysfunctions of persistent unemployment, poverty and lack of education among some residents.

Henry Smith was an African-American youth who was lynched in Paris, Texas. Smith allegedly confessed to murdering the three-year-old daughter of a law enforcement officer who had allegedly beaten him during an arrest. Smith fled, but was recaptured after a nationwide manhunt. He was then returned to Paris, where he was turned over to a mob and burned at the stake. His lynching was covered by The New York Times and attracted national publicity.

Robert Paul Prager was a German immigrant who was lynched in the United States during World War I as a result of anti-German sentiment. He worked as a baker in southern Illinois and then as a laborer in a coal mine, settling in Collinsville, a center of mining. At a time of rising anti-German sentiment, he was rejected for membership in the Maryville, Illinois local of the United Mine Workers of America. Afterward he angered area mine workers by posting copies of his letter around town that complained of his rejection and criticized the local president.

White caps were groups involved in the whitecapping movement who were operating in southern Indiana in the late 19th century. They engaged in vigilante justice and lynchings, with modern viewpoints describing their actions as domestic terrorism. They became common in the state following the American Civil War and lasted until the turn of the 20th century. White caps were especially active in Crawford and neighboring counties in the late 1880s. Several members of the Reno Gang were lynched in 1868, causing an international incident. Some of the members had been extradited to the United States from Canada and were supposed to be under federal protection. Lynchings continued against other criminals, but when two possibly innocent men were killed in Corydon in 1889, Indiana responded by cracking down on the white cap vigilante groups, beginning in the administration of Isaac P. Gray.

From 1967 to 1973, an extended period of racial unrest occurred in the town of Cairo, Illinois. The city had long had racial tensions which boiled over after a black soldier was found hanged in his jail cell. Over the next several years, fire bombings, racially charged boycotts and shootouts were common place in Cairo, with 170 nights of gunfire reported in 1969 alone.

In the early hours of 3 June 1893, a black day-laborer named Samuel J. Bush was forcibly taken from the Macon County, Illinois, jail and lynched. Mr. Bush stood accused of raping Minnie Cameron Vest, a white woman, who lived in the nearby town of Mount Zion.

David Wyatt was an African-American teacher in Brooklyn, Illinois. In June 1903, Wyatt was denied renewal for his teaching certificate by the district superintendent, Charles Hertel. After hearing about his denial, Wyatt shot Hertel and was immediately arrested. While in jail, a mob captured Wyatt, lynched him in the public square, and set his body on fire.

On April 13, 1937, Roosevelt Townes and Robert McDaniels, two black men, were lynched in Duck Hill, Mississippi by a white mob after being labeled as the murderers of a white storekeeper. They had only been legally accused of the crime a few minutes before they were kidnapped from the courthouse, chained to trees, and tortured with a blow torch. Following the torture, McDaniels was shot to death and Townes was burned alive.

Ephraim Grizzard and Henry Grizzard were African-American brothers who were lynched in Middle Tennessee in April 1892 as suspects in the assaults on two white sisters. Henry Grizzard was hanged by a white mob on April 24 near the house of the young women in Goodlettsville, Tennessee.

La Matanza and the Hora de Sangre was a period of anti-Mexican violence in Texas, including massacres and lynchings, between 1910 and 1920 in the midst of tensions between the United States and Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. This violence was committed by Anglo-Texan vigilantes, and law enforcement, such as the Texas Rangers, during operations against bandit raids known as the Bandit Wars. The violence and denial of civil liberties during this period was justified by racism. Ranger violence reached its peak from 1915 to 1919, in response to increasing conflict, initially because of the Plan de San Diego, by Mexican and Tejano insurgents to take Texas. This period was referred to as the Hora de Sangre by Mexicans in South Texas, many of whom fled to Mexico to escape the violence. Estimates for the number of Mexican Americans killed in the violence in Texas during the 1910s, ranges from 300 to 5,000 killed. At least 100 Mexican Americans were lynched in the 1910s, many in Texas. Many murders were concealed and went unreported, with some in South Texas, suspected by Rangers of supporting rebels, being placed on blacklists and often "disappearing".

In November 1902, a white mob from Sullivan and Knox counties lynched James Dillard, a young Black man from Indianapolis. Dillard's death resulted in a lengthy legal battle over Indiana's 1899 anti-lynching law.